CHAPTER 1 :

Chapter one

THE U.S. GOVERNMENT’S RENDITION, DETENTION, AND INTERROGATION (RDI) PROGRAM

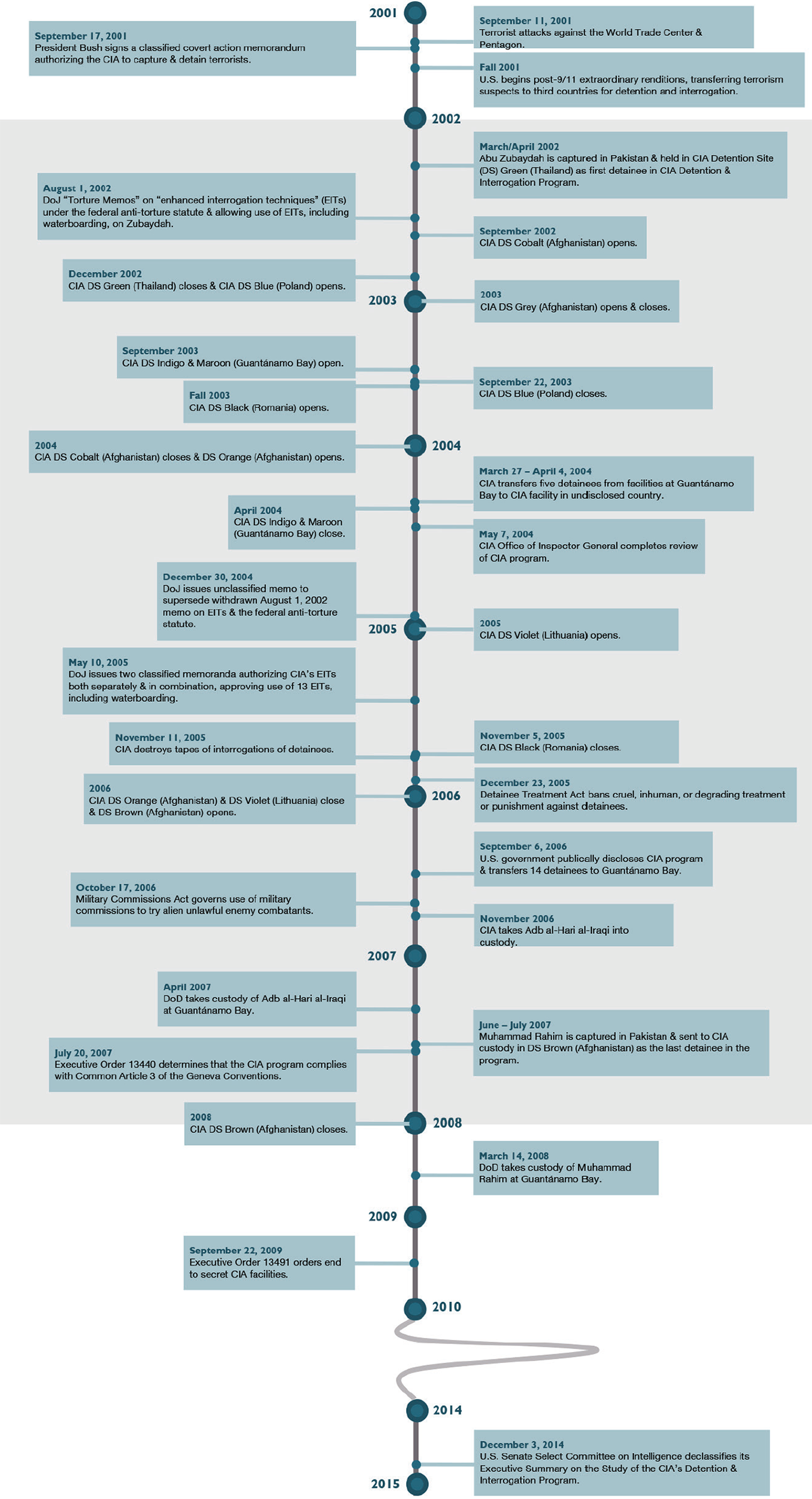

On September 17, 2001, in the aftermath of the events of September 11, President Bush signed a classified, covert action memorandum authorizing the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to seize and detain suspected terrorists.100 By the following month, October 2001, Aero Contractors, Limited (“Aero”) had begun to operate a Gulfstream V turbojet, aircraft N379P, out of North Carolina in the United States to secretly transfer individuals suspected of terrorism between countries and jurisdictions without legal process.101 The program was only suspended by Executive Order 13491 in 2009.102 This chapter of the report provides an overview of the program, with special attention to the partnerships that made it possible.

Aero’s N379P was one of multiple airplanes used in the CIA operations. “Rendition” is an umbrella term that refers to any transfer of a person between governments.103 “Extraordinary rendition” is the secret and forcible transfer of an individual between States or legal jurisdictions outside of the law. Through the RDI program of extraordinary rendition, the U.S. government worked with private U.S. corporations, such as Aero, and foreign agents to transfer suspected terrorists through two interlinked detention systems for coercive interrogation. The flights carried suspected terrorists either to foreign (non-U.S.) custody or to CIA custody in CIA-run secret prisons or “black sites.”104 The program of transferring individuals to and among these two systems for interrogations using torture is referred to in this report by the CIA’s name: the Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation (RDI) program.

Aero Contractors security gate at Johnston County Airport.

Photo courtesy: NCSTN

The RDI program developed out of the U.S. law enforcement practice of “rendition to justice” of the late 1980s and 1990s, in which “suspects were apprehended by covert CIA or FBI teams and brought to the United States or other states (usually the states having an interest in bringing the person to justice) for trial or questioning.”105 In the new RDI program, however, the CIA gained unprecedented authority to operate its own “black sites.”

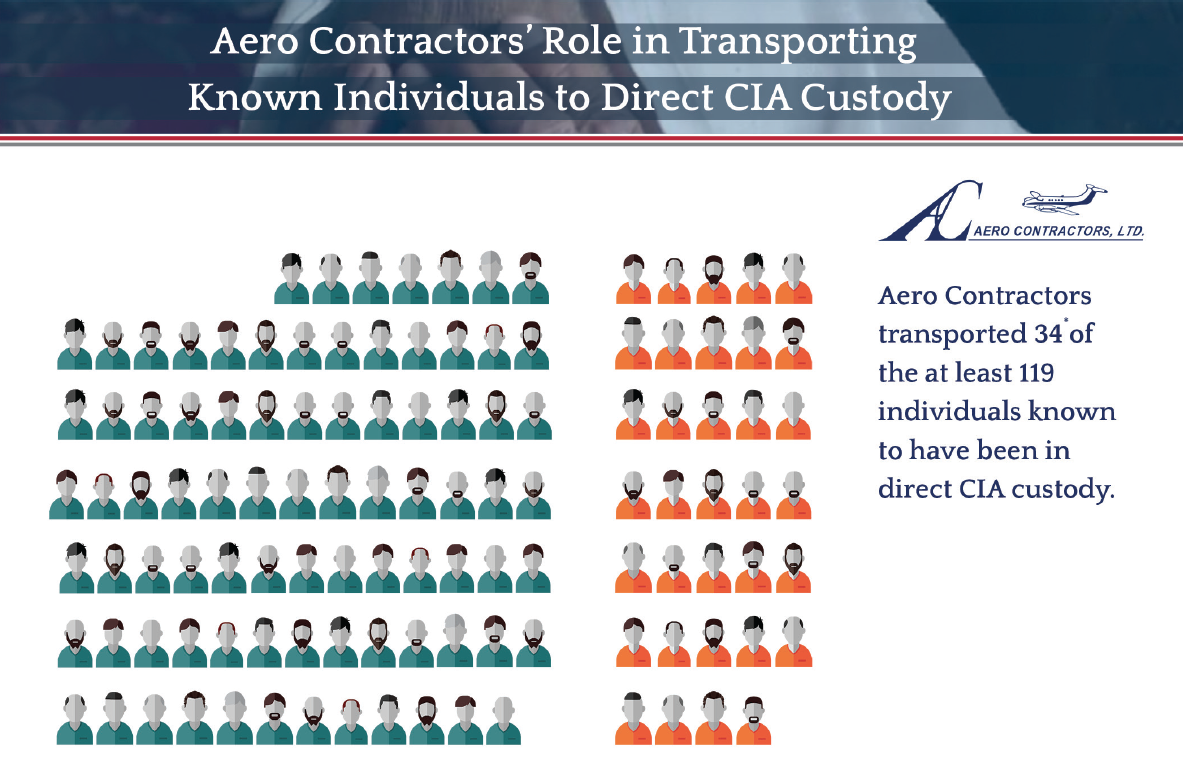

What is known is that the SSCI inquiry found “at least 26” of the CIA’s estimated 119 detainees were victims of mistaken identity or other errors, a tally that reflects only those determined by the CIA itself not to meet its criterion for detention.108 Among these 26 are individuals who were rendered on Aero-operated flights.109

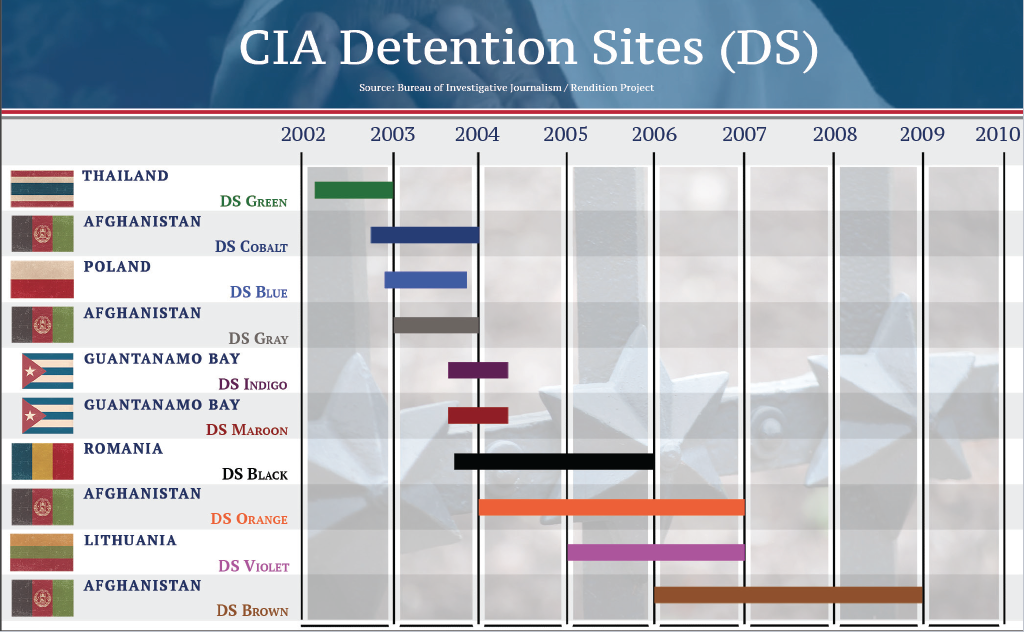

Transferring individuals to foreign custody was an “integral component of the CIA program.”111 The U.S. government handed individuals over for coercive interrogation by intelligence agencies in countries such as Egypt and Jordan.112 Starting with the apprehension of Abu Zubaydah in March 2002,113 the U.S. government also began to render individuals to CIA-run prisons. Between 2002 and 2008, the CIA would go on to hold at least 119 individuals114 in ten CIA “black sites” in six countries around the globe: one in Thailand, one in Poland, one in Romania, one in Lithuania, two in Guantánamo Bay, and four in Afghanistan.115 Because the CIA ran a “black site” network throughout the RDI program, detainees were often transferred multiple times between these various sites, as well as to foreign custody, during their detention.

According to U.S. government documents, upon abducting targeted individuals, rendition teams prepared them for flight by hooding them, performing body cavity searches, applying ankle and wrist restraints, and administering sedation, all without permission or explanation.

According to U.S. government documents, upon abducting targeted individuals, rendition teams prepared them for flight by hooding them, performing body cavity searches, applying ankle and wrist restraints, and administering sedation, all without permission or explanation.116 The CIA considered abduction and rendition to be integral to the interrogation process by making detainees disoriented, helpless, and afraid. The protocols of rendition (discussed further in Chapters 4 and 5 of this report) “generally create[d] significant apprehension in the [detainee] because of the enormity and suddenness of the change in environment, the uncertainty about what will happen next, and the potential dread [a detainee] might have of U.S. custody.”117

Source: Color Keys for Detention Sites from the Senate Intelligence Committee Reports on Detention and Interrogation Program Infographic: Christian Johnson, XianStudio

Once in CIA “black sites,” individuals were tortured through so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques” (EITs), including facial slaps, waterboarding, solitary confinement, wall standing, stress positions, sleep deprivation, diapering, rectal feeding, and use of insects.118 Such techniques could be as repetitive as they were torturous. For example, one CIA detainee, Khalid Shaikh Muhammad, was subjected to “183 applications of the waterboard”119 on 15 different documented occasions.120

Overview of the CIA Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation Program Between 2002 and 2008, the CIA held at least 119 detainees in ten CIA prisons in six

country locations and transferred an unknown number of terrorism suspects to third countries for detention and interrogation. Aero Contractors, Inc. transported 34 of the detainees that were

sent to CIA prisons and nine of the individuals transferred to custody of third countries. ‘ENHANCED INTERROGATION TECHNIQUES (EIT)’

Designed by two military psychologists who sought to instill a sense of learned helplessness among detainees, in which individuals would become “passive and depressed in response to adverse or uncontrollable events,”121 EITs, often used in conjunction, included:

These brutal techniques are considered acts of torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment and are illegal under U.S. and International Law.122

BEYOND THE CIA: FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE ACTORS, AND U.S. LOCAL AND STATE OFFICIALS

Three main entities carried out the post-9/11 RDI program: the U.S. government, foreign governments, and private actors. Both of the interconnected systems of extraordinary rendition and CIA secret detention relied heavily on the co-operation of foreign governments that were willing to provide structural support and personnel. Reflecting the reliance of the U.S. government on these foreign partners, a Council of Europe inquiry into “Alleged secret detentions and unlawful inter-state transfers involving Council of Europe member states” described the CIA’s program as a “network that resembles a ‘spider’s web’ spun across the globe.” According to testimony before the NCCIT, foreign governments participated in the RDI program by: 128

Private actors were ubiquitous in the U.S. government’s post-9/11 RDI program. To design the program, the CIA contracted two psychologists, James Mitchell and John “Bruce” Jessen, to devise its interrogation tactics. Shortly after the psychologists “formed a company specifically for the purpose of conducting their work with the CIA” in 2005, the “CIA outsourced virtually all aspects of the program.”129 Private aircraft companies also played a central role, primarily in the transport of individuals as well as in providing other associated logistical support.

The CIA rendition aircraft N379P Photo courtesy: Fred Seggie | World Air Images | Airliners.net

The second system, in place from 2002 to 2006,133 also relied on private companies and was organized through a “prime contract” between the CIA and DynCorp Systems and Solutions, LLC (and its corporate successor Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC)).134 Through this arrangement, DynCorp/CSC entered into agreements with aircraft brokers that in turn contracted with aircraft operating companies to supply the planes.135

In the first phase of extraordinary rendition when individuals were transported to foreign custody, the use of civilian aircraft owned by shell companies and operated by private entities was critical to the covert nature of the program. It enabled “the CIA [to] avoid] the duty to provide the information required by States concerning government or military flights.”136 Of these real private companies, North Carolina-based Aero was particularly critical to the RDI program. According to testimony provided to the NCCIT, “[i]t is now clear that Aero Contractors aircraft played an absolutely central role in the CIA’s torture program especially during the first years of its operation.”137 Indeed, Aero operated-aircraft, the Gulfstream V N379P and Boeing 737 N313P conducted “over 80%” of identified U.S. government renditions between September 2001 and March 2004.138

NORTH CAROLINA AND THE RDI PROGRAM:

Despite the myriad crimes associated with the RDI program, no U.S. executive agency nor any U.S. state has held accountable anyone involved in the RDI program. Domestically, efforts to ensure accountability, including for North Carolina’s role in the RDI program, have been frustrated on many levels. Chapter 8 of this report examines the extensive role that North Carolinians have played in continuing to press for transparency and an end to torture.

Source: Senate Intelligence Committee, Bureau of Investigative Journalism / Rendition Project Infographic: Christian Johnson, XianStudio

With respect to Congress, on December 9, 2014, the SSCI released a redacted version of its declassified Executive Summary on the Study of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program.147 But the full study, which was the product of more than five years of investigation and totals more than 6,700 pages, remains classified. Additionally, because that inquiry was focused at the federal government level, it does not examine the role of states such as North Carolina, upon whose participation the program depended.

Transparency and accountability for illegal and immoral components of the

RDI program require full disclosure of the role of states within the United States;

the contribution of private companies to official rendition, detention,

and interrogation; the routes and processes of rendition;

and the full identities and fates of those affected.

Cases involving rendition victims — including several individuals transported on Aero-operated flights — have for the most part not proceeded in U.S. courts because the U.S. government has argued they should be dismissed on the basis of the “state secrets” privilege, in order to protect national security. When applied too broadly, this argument can prohibit accountability for illegal government actions. For example, on December 6, 2005, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a lawsuit against former Director of the CIA George Tenet, three private aviation companies (including Aero Contractors), and several unnamed defendants in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. The suit, which was ultimately unsuccessful,148 concerned the rendition of Khaled El-Masri from Skopje, Macedonia to Afghanistan on N313P.149 On May 30, 2007, the ACLU filed another lawsuit that was also ultimately unsuccessful150 against Jeppesen Dataplan, Inc. in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California on behalf of three victims of the “extraordinary rendition” program.151 The complaint was amended August 1, 2007 to add two additional victims.152 All five victims had been transported on aircraft N379P and N313P.153

Source: Bureau of Investigative Journalism / Rendition Project Infographic: Christian Johnson, XianStudio

Although the RDI program ended in 2009 and its initial legal underpinnings have been rescinded, there remain significant information and accountability gaps regarding the program’s scope, participants, and effects. Transparency and accountability for illegal and immoral components of the RDI program require full disclosure of the role of states within the United States; the contribution of private companies to official rendition, detention, and interrogation; the routes and processes of rendition; and a full accounting of the fates of those affected.

CONCLUSION There have been serious failures and omissions of transparency and accountability with respect to the U.S. post-9/11 program of extraordinary rendition, secret detention, and torture. The important, yet partial, official transparency that has occurred involves solely the CIA black site portion of the program. No formal accounting has occurred of those individuals transferred by the CIA to foreign custody for torture and unlawful detention. Nor has there been official accounting for the very significant role of private actors such as Aero Contractors in the RDI program. The lack of transparency and accountability undercuts the rule of law at the state and federal level.

According to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) inquiry into the CIA’s detention and interrogation program, the CIA held at least 119 individuals in direct CIA custody between 2002 and 2008.106 However, expert testimony before the North Carolina Commission of Inquiry on Torture (NCCIT) indicates that the actual number of individuals affected by the program is likely far higher. This is because of poor record keeping on the part of the CIA, the lack of research on and acknowledgment of detainees rendered to foreign custody, and knowledge of additional detainee renditions without corresponding flight paths, which indicates the existence of additional rendition aircraft.107 Therefore, the true number of individuals subject to the RDI program — and in particular the number, identities, and whereabouts of those rendered to foreign custody for detention or interrogation — remains unknown.

Torture and ill-treatment were hallmarks of rendition to both foreign government custody and CIA secret detention. The “two programs entailed the abduction and disappearance of detainees and their extra-legal transfer on secret flights to undisclosed locations around the world, followed by their incommunicado detention, interrogation, torture, and abuse.”110

According to official figures, “at least 39” of the at least 119 individuals in CIA custody were subject to EITs.123 However, the actual identities, numbers, and whereabouts of individuals in the CIA program and those subject to torture and abuse remain unknown because the CIA “never conducted a comprehensive audit or developed a complete and accurate list of the individuals it had detained or subjected to its enhanced interrogation techniques.”124 Nor is the scope of detainee experience fully documented, given that detainees faced “harsher”125 confinement conditions and interrogations that were “brutal and far worse”126 than what the CIA had officially indicated to policymakers and other government officials.

Individuals rendered to foreign government custody similarly faced torture and other abuse. According to one U.S. official involved in rendering individuals to foreign governments: “We don’t kick the [expletive] out of them. We send them to other countries so they can kick the [expletive] out of them.”127

Post-9/11, the U.S. government utilized two distinct and parallel aviation systems that involved private actors to transport individuals to foreign custody and/or to CIA custody.130 The first system, lasting from 2001 to 2004, involved the use of planes owned by CIA shell companies (e.g., Stevens Express Leasing, Inc.; Premier Executive Transport Services, Inc. (PETS); Rapid Air Transport, Inc.; Path Corporation; Aviation Specialties).131 These planes were typically operated by a series of real companies (such as Aero Contractors, Limited, Pegasus Technologies, and Tepper Aviation), that were responsible for “maintenance, providing hangars and arranging the logistical details for each flight circuit.”132

Trip planning services for “a number of” identified rendition circuits on Aero-operated aircraft N313P and N379P were provided by Jeppesen Dataplan, Inc.,139 a company with headquarters in San Jose, California.140 The role of Jeppesen Dataplan, Inc. is described in a 2007 federal lawsuit on behalf of five extraordinary rendition victims against the company. The lawsuit states that “in knowingly providing flight and logistical services to the CIA for the rendition program, the company facilitated and profited from Plaintiffs’ forced disappearances, torture, and other inhumane treatment.”141

As is further described in Chapters 2 and 8, within the United States, host states for these private companies also enabled these abuses, including by allowing companies to use public airports and by failing to investigate allegations about the use of public resources to

this end.

GAPS IN INFORMATION AND ACCOUNTABILITY

With respect to intra-agency accountability, at the time of the program’s operation, the “CIA avoided, resisted, and otherwise impeded oversight of the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation Program by the CIA’s Office of Inspector General.”142 While the May 2004 report by that same office contains some criticism of the CTC (Counterterrorist Center) Detention and Interrogation Program,143 it nonetheless concludes that there is no need for “separate investigations or administrative action.”144 Other agency actions that impeded accountability include the CIA’s destruction of tapes documenting CIA interrogation in November 2005.145 An investigation into the tapes’ destruction ended without bringing criminal charges against participants.146

In addition, investigation of the treatment of these individuals that were rendered by the CIA to foreign custody for interrogation by allied intelligence services is still needed. The SCCI inquiry focused solely on those that were brought directly to CIA custody, meaning that “there’s still no official account of the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of other victims of torture that the CIA is responsible for.”154

This failure to provide justice for victims of the RDI program and accounting of what happened is far from inevitable. Outside of the United States, the role of North Carolina and private entities in the RDI program — and the illegality of their actions — have been in both the public eye and scrutinized by courts and other legal institutions. For example: